During the period 2020-2023, we listened to the news describing the stark maternal morbidity and mortality statistics that Black women experience. We read about the mistreatment that Black women and birthing people from all social backgrounds experienced during maternity care. Films such as Aftershock and Birthing Justice were putting names, faces, and lives behind the statistics. They were also showing how families were rising to the challenge the systems that normalized that harm.

2023

We began to document the answer to a simple question: “What is the Black community doing to address this crisis?” We were interested in solutions that communities were developing to mitigate or even circumvent the harm. Our shared conviction is that Black communities are creative, resourceful, and capable of leading themselves. We believe that the dominant medical system is limited in its ability to enact the transformation that was needed to address the systemic and inherent inadequacies in the provision of care. We’re especially interested in the perspectives of leaders, practitioners, and activists who were building new systems of care outside the dominant system.

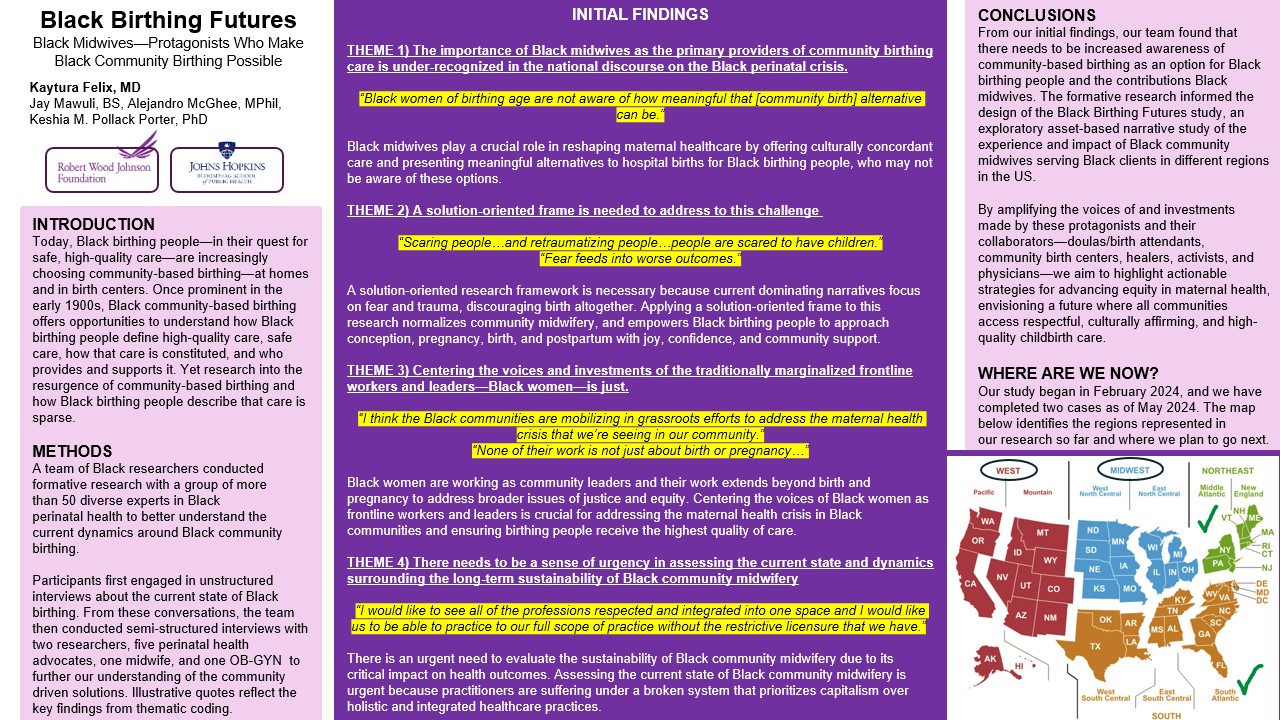

Our team engaged 58 experts, leaders, and practitioners, who were all committed to improving Black maternal health. We wanted to learn about the community’s response and innovation to address the challenge. The following themes emerged:

It appeared to many that the health establishment was more interested in “admiring the problem” or wringing their hands than in highlighting solutions. We learned that stoking fear around pregnancy and birthing for Black people produced adverse outcomes.

We learned that Black women were on the frontlines on innovations to address community challenges. Their holistic approach includes addressing the multiple social and economic factors driving the perinatal crisis. Given Black women’s expertise and track record in this domain, highlighting and resourcing their efforts was imperative.

We learned that Black community midwifery is under-recognized and consequently under-resourced. Black community midwives provide care to Black birthing people in homes and birth centers, thereby providing an alternative to the hospital-based model of care.

This led us to design the Black Birthing Futures (BBF) study, an in-depth case study of the experiences and impacts of Black midwives on their Black clients across the U.S. The overall goal of this project is to increase safe and effective birthing options for Black people by bringing attention and resources to community birthing.

This study is funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

BBF is an asset-based narrative analysis study that seeks to:

- Describe the unique aspects of the care that Black midwifes provide to Black birthing people outside the hospital

- Identify the environmental conditions that support or hinder that type of practice

- Describe the impact of this type of practice on families and communities.

2024

Between March and September 2024, our team achieved the following:

We interviewed Black community midwives and the members of their ecosystem to get an in-depth picture of the care these midwives provide.

These members included Black birthing clients receiving care from said midwives, clients’ family members, midwives’ collaborating providers, community stakeholders, and midwives’ family members.

We also observed midwifery visits to Black clients during the prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum period. These locations of these visits included midwifery offices, client’s homes, and birth centers.

And finally, we surveyed clients about their abilities to exercise their autonomy and decision making as well as to be respect in the care that they received from Black community midwives. We utilized the My Autonomy in Decision Making Scale (MADM) and Measures of Respect Index (MOR) for these surveys courtesy of The Birth Place Lab.

Our Key Takeaways

Our study found that Black community midwives provided restorative, person-centered care to their clients that went beyond medical services to include nutrition and physical activity counseling, deep care that was familial, pregnancy education, integration of family members or companion into the visit, and community building activities. Their clients expressed appreciation for holistic care, especially for the inclusion of their families in their care.

Clients also reported that their midwifery care empowered them to better advocate for themselves and to hold mainstream medical providers to the high standards set by their midwives. Clients’ barriers included high out of pocket costs, lack of available information on community midwifery, lack of knowledge and misinformation regarding clients’ eligibility for community midwifery care, and mistreatment upon transfer to hospital care.

Midwives’ barriers included high cost and inadequate institutional support for training, maintaining a financially viable practice which providing access to Black clients, and hospital staff’s disrespect and lack of regard for their knowledge and expertise. In states that licensed direct entry midwives, administrative barriers kept them from participating in Medicaid and private insurance programs despite their commitment to that population. Midwives, clients, clients’ families, collaborating providers and others recommended policy reforms and public education to increase access to community midwives and improve their integration into the health care system.

Why this study is important?

Our study contributes a strengths-based approach to birth care in the U.S., actively focusing on efforts being made in the Black community as opposed to observing maternal mortality rates. Policymakers, community midwives, and diverse stakeholders must collaborate to strengthen community-based efforts that aim to redress structural racism in American healthcare. By focusing on the solutions community members are taking, our study elevates the voices unheard that are proposing a better future for Black birthing people.